On the afternoon of Monday, 4 April 2011, Juliano Mer-Khamis walked out of the Freedom Theatre in the Jenin refugee camp and got into his old red Citroën. It was four o’clock, the sun was hot and the street crowded. He put his baby son, Jay, on his lap, placing the boy’s fingers on the steering wheel; the babysitter sat next to them. As he set off, a man in a balaclava came out of an alleyway and told him to stop. He had a gun. The babysitter told Juliano to keep driving, but he stopped. The gunman shot him five times, then walked back down the alley. He left his mask in the street. Jay survived; the babysitter escaped with minor injuries. Juliano was dead. Later his body was handed over to the Israeli authorities, along with his car, computer, wallet and other effects.

Juliano was the founder of the Freedom Theatre. He was an Israeli citizen, the son of a Jewish mother and therefore a Jew in the eyes of the Jewish state. But his father was a Palestinian from Nazareth, and Juliano was a passionate believer in the Palestinian cause. He would often say he was ‘100 per cent Palestinian and 100 per cent Jewish’, but in Israel he was seldom allowed to forget he was the son of an Arab, and in Jenin he was seen as an Israeli, a Jew, no matter how much he did for the camp. Among the artists and intellectuals of Ramallah, however, he was admired for having left Israel to work in one of the toughest parts of the West Bank, and was accepted as an ally. Since its founding in 2006, the Freedom Theatre had been under constant fire: local conservatives saw it as a corrupting influence, even a Zionist conspiracy; the Palestinian Authority resented what Juliano said about its ‘co-operation’ with Israel; and Israel saw him as a troublemaker, if not a traitor.

Shortly after the murder, Mahmoud Abbas declared Juliano a shaheed, a martyr. But though he may have given his life to the Palestinian cause, he was not killed by an Israeli bullet. The man who shot him was Palestinian, and probably from the camp: no one else would have known how to navigate those streets, or how to disappear so quickly. The killing appeared to be a message from forces inside the camp. Juliano had spoken bluntly about the stifling effects of patriarchy, gender oppression and religious dogma; freedom, he argued, began with individual liberation, and without it freedom from occupation would mean nothing. This did not endear him to defenders of ‘tradition’. Nor did the theatre’s productions, in which teenage boys and girls appeared on stage together. But risk was part of what inspired Juliano. In a 2008 interview, he joked that he would be killed by a ‘fucked-up Palestinian’ for ‘corrupting the youth of Islam’. The interview was posted on YouTube shortly after his murder.1

The silence from the camp seemed to confirm the hypothesis: few people beyond those involved with the theatre mourned Juliano, and no one came forward to identify the killer. For Israel’s radical left, the murder was a devastating blow. Handsome and charismatic, Juliano was a symbol of the binational dream, a walking advertisement for solidarity and coexistence. For Palestinian artists and intellectuals his murder was ‘a hammer in the head’, as George Ibrahim, head of the Qasaba Theatre in Ramallah, put it. But right-wing commentators in Israel were delighted that a pro-Palestinian celebrity had been killed by a Palestinian. ‘He lived among snakes, and one of them killed him with its bites,’ Yehuda Dror wrote. ‘He proves to us once more that there is no one to talk to.’

When I visited Jenin two months after the murder, almost everyone agreed that Juliano had angered many people in the camp, in spite of his efforts to win them over to his programme of ‘cultural resistance’ as he called it. No one was going to the theatre, and the six members of his graduating class had left Jenin for Ramallah. The actor Nabil al-Raee, the theatre’s artistic director, and his wife, Micaela Miranda, an actress from Portugal, were working out of the house they had shared with Juliano and his family. They weren’t sure when they would return to the theatre, or whether it would survive. Nawal Staiti, an old friend of Juliano’s, wouldn’t get out of the car when she drove me to the theatre. ‘I blame the camp,’ she said, bursting into tears. ‘They know who killed Juliano, and they aren’t saying.’

Two years after his murder, the theatre Juliano created still stands in a converted stone house rented from the UN. But until the murder is solved, al-Raee told me, ‘we remain under threat.’ The question is from whom? Al-Raee no longer believes that Juliano was killed for challenging the ways of the camp; he thinks the killer was a hired hand, acting on behalf of more powerful forces inside the PA and Israel. At the theatre, Juliano was seen as a political leader, not just a director: therefore his killing must have been an assassination. But elsewhere, one hears other theories, mostly to do with money, corruption and factional struggles. These theories have taken on a life of their own. The idea that Juliano was killed for introducing transgressive Western ideas about personal liberty to a community that adheres to a conservative form of Islam is no longer popular, except among Israeli Jews for whom it confirms old prejudices. As people in Jenin will tell you, violence against solidarity activists, even if they are Israeli, is almost unheard of in Palestine. That’s what made the killing so unsettling.

It’s possible, of course, that Juliano’s murder had little to do with his work and more to do with the man himself. The most important question may not be who killed him, but why his killer, or killers, believed they could eliminate him with impunity. Whoever killed him knew that no one in the camp would rush to his defence. Juliano loved the camp – no one doubts that. But he seemed to forget that he was a guest there, and that the more deeply he penetrated the life of the camp, the more cautiously he had to tread.

Juliano was the son of one of Jenin’s most famous guests, Arna Mer, and many people will always remember him as her son. Arna Mer’s work with children in the camp had made her a legendary figure. Born in 1929, she came from the Zionist aristocracy: her father, Gideon Mer, briefly directed Israel’s ministry of health in the mid-1950s. At 18 she joined the Palmach, the Jewish fighting brigades, and drove a jeep during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. It was thrilling, she told Juliano in the documentary he made about her, Arna’s Children, to be a young woman ‘driving people from place to place, and nobody could stop you’. She would remain a Palmachnik – tough-talking, sometimes arrogant, always brutally direct – and she passed the style on to Juliano. The keffiyeh she wore in Jenin, which Palestinians assumed to be an expression of solidarity, was a homage to her days in the Palmach, when Zionists adopted the look of the fellahin whose land they coveted.

Arna became disillusioned with Zionism after taking part in an operation to drive the bedouin out of southern Palestine. Shortly after the war, she joined the Communist Party. She met Saliba Khamis, an intellectual from a Greek Orthodox family, at a party conference. Khamis was an emerging leader in ‘Red Nazareth’, where the party was attracting support for protesting against Israel’s harsh military government. Arna and Saliba married in 1953. To be in a mixed marriage was to be a good Communist; it expressed opposition to Zionism, and honoured the principles of internationalism. Outside the party, and particularly among Jews, a mixed marriage was a source of unspeakable shame. Arna’s father saw it as an act of rebellion that even he, a socialist, could not countenance. She was welcomed into the Khamis family, and shunned by her own.

Juliano, born in 1958, was the second of their three sons, and grew up in Nazareth and Haifa. It was a political household: Saliba wrote pieces in the party newspaper, Al-Ittihad, about the rise of anti-colonial liberation movements; Arna had been a teacher but was fired for marrying an Arab, and spearheaded a popular campaign against the military government. The marriage was difficult. Arna was at heart an anarchist; Saliba a party man who was growing embittered at being denied a seat in the politburo. They disagreed fiercely about how to raise their sons: Saliba wanted them to be clean-cut young Communists, and was furious when Arna allowed them to grow their hair long. ‘Juliano grew up with a paradox,’ Osnat Trabelsi, the producer of Arna’s Children, told me. ‘Outside, the oppressor was the Jew, but at home, the oppressor was Arab.’ Juliano later said he first learned about politics ‘at the end of my father’s belt’. When Juliano was ten, Saliba moved out. Juliano attended Jewish schools in Haifa and saw himself as a Jew – he even stopped speaking Arabic for a time. At the age of 18, he joined the paratroopers. Saliba and Arna were horrified: Juliano was now a soldier in the occupation they had both devoted their lives to fighting. He was stationed in Jenin.

Jenin has had a reputation for defiance since the Ottoman era, when residents refused to pay taxes to the sultan. Seized from Jordan on the first day of the 1967 war, it soon became a centre of resistance to the Israeli occupation: the camp, which was set up in the early 1950s as a temporary shelter for refugees from Haifa and the neighbouring villages, was known to be especially militant. By the time Juliano was stationed there, it had evolved into a concrete slum where more than ten thousand people were squeezed into a space not much bigger than five hundred square metres. If a soldier killed an old woman or a child by accident a weapon would be planted on the corpse: Juliano’s job was to carry the bag with the weapons. One night they were trying out new shoulder-fired missiles. They shot at a donkey, but instead killed the 12-year-old girl who was sitting on it. Explosives from the black bag were laid on top of the donkey.

It wasn’t long before he cracked. At a checkpoint in Jenin, his commanding officer asked him to search an elderly Palestinian man. Later he would claim that the man was a cousin, though he had never seen him before. No one disputes what happened next: Juliano refused his orders, punched his commanding officer and spent several months in prison. He would have been there longer had Arna not called Isser Harel, her cousin and the first head of the Mossad, and implored him to get her son released. He recovered in a mental hospital. His life as an Israeli Jew was over. He now flirted with the idea of joining the PLO: he still wanted to be a soldier, whatever side he was on. But he was no good at following orders. Instead, he enrolled at the Beit-Zvi School for the Performing Arts in Tel Aviv. There he could be an Arab or a Jew, or neither.

In 1985 Juliano Mer – he dropped ‘Khamis’ from his name – starred in Amos Guttman’s film Bar 51, a tale of obsessive love between a brother and sister, set in Tel Aviv’s hedonistic underground. He seemed poised to become a star of Israel’s emerging independent cinema. ‘Juliano had the material of great actors,’ Amos Gitai, who cast him in seven films, told me. But he was looking for something more intense. In 1987 he went to the Philippines, where he spent a year, mostly high on mushrooms. He lived in a tent, talked to monkeys and declared himself the son of God. His parents had him rescued. But he felt that something important had happened to him under the influence of the mushrooms: ‘I lost all my identities.’ As an actor this was no bad thing: ‘I have a gift, you are not only consciously un-nationalised, you are inside yourself divided. Use it!’ He took the idea to the streets. In downtown Tel Aviv he would remove his clothes, cover himself in fake blood or olive oil or paint, and denounce Israel’s response to the First Intifada, which had just broken out.2 His performances in Palestinian refugee camps were physically more demure but scarcely less provocative. ‘They think that if you replace the Israeli occupation with the Arafat occupation, it’s going to be better,’ he said, ‘and I say no, fight both of them!’

He was sleeping on the beach, eating nothing but olives, labneh and garlic. He was saved by two women. The first was Mishmish Or, who found him one night in a bar wearing only his underwear. She was an Israeli Jew in her mid-twenties, the daughter of a Turkish father and an Egyptian mother, a costume designer, and the mother of a two-year-old daughter, Keshet. She took him home that night; he moved in, and became a stepfather to Keshet. The second was his mother, who asked him to help out with her new project. When the Israeli army shut down Palestinian schools after the outbreak of the intifada, Arna went to Jenin. ‘I have not come here for philanthropic reasons,’ she said, or to ‘show that there are nice Jews who help Arabs. I came to struggle against the Israeli occupation.’ Working closely with Nawal Staiti and Samira Zubeidi, both of them married to Fatah militants who were in and out of prison, Arna established an alternative education system called Care and Learning. She brought toys to people’s homes, and distributed banned resistance pamphlets. Israeli, Jewish, a former member of the Palmach and an atheist: everything about Arna was wrong in Jenin. But the parents of Jenin’s children loved her.

More than 1500 students from the camp attended her ‘children’s centres’, most of which were run out of people’s homes. Arna, an accomplished sculptor, believed art could provide the children with a means of expressing their feelings about the occupation. She invited Juliano to teach drama therapy. And when she received the so-called alternative Nobel, the Right Livelihood Prize in Sweden, she built a theatre with the proceeds. In 1993, the Stone Theatre, named after the stones children threw at Israeli tanks, was established on the top floor of Samira Zubeidi’s house. Juliano was there constantly, directing rehearsals, and filming his mother and the children for what became Arna’s Children. The Stone Theatre reunited the family: Saliba and Juliano’s brothers came to performances, and Juliano began to call himself Mer-Khamis again. At first his students looked at him warily; they worried he might be ‘a spy for the occupation’, as one of them told him. But he formed lasting friendships – among them with Samira Zubeidi’s son Zacharia, who would later become a leader of the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, a militia of young men affiliated with Fatah, and a co-founder of the Freedom Theatre.

Arna died of cancer in 1995, a few months after Saliba Khamis. No cemetery would bury her: she was now a traitor for her activities in Jenin. Juliano held a press conference at her home in Haifa. He said he would bury her in her garden if nowhere else would have her. Finally Ramot Menashe, a left-Zionist kibbutz in the hills of the Carmel, offered to take her. Juliano didn’t set foot in Jenin for another seven years. He returned to his old life, and made a name for himself as a daringly physical performer in Tel Aviv’s Habima Theatre. He played the gay prisoner in Kiss of the Spider Woman; he performed in Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge and Tony Kushner’s Angels in America. As Othello, he nearly strangled the actress playing Desdemona: an ambulance had to be called to resuscitate her. He often got into brawls: with directors, actors, even members of the audience.

But he was also settling down. In 2000, Or gave birth to their daughter Milay; along with Keshet they moved into Arna’s old house in Haifa. But soon after the Second Intifada erupted in October 2000 Juliano turned their house into a base for organising. This intifada, unlike the first, was armed, and Jenin was leading the way. Over the next three years, militants inside the camp – the ‘capital of terror’, according to Israeli tabloids – sent an estimated thirty suicide bombers to Israel. In October 2001, two of Juliano’s former students, Yusuf Sweitat and Nidal al-Jabali, carried out an attack. Two weeks earlier, Sweitat had rescued a girl from her classroom where an Israeli shell had exploded; she died as he was carrying her to hospital. Vowing to avenge her death, he and al-Jabali offered their services to Islamic Jihad. They drove a stolen jeep to a bus station in Hadera and opened fire. Four women were killed before the police killed Sweitat and al-Jabali.

Sweitat had been one of Juliano’s favourite students. When he heard what had happened, Juliano decided to return to Jenin with his camera and complete the film about his mother. His first trip back was in May 2002; a month earlier, on 2 April, more than a thousand soldiers had surrounded the camp and declared it a closed military zone. As the soldiers approached, Zacharia Zubeidi, speaking in Hebrew through a loudspeaker, warned them not to enter. The fighting went on for two weeks. The army demolished parts of the camp with armoured bulldozers, supported by tanks. In the end, the camp lay in ruins. When Juliano arrived with two generators there had been no electricity for more than a month. His host was his former student Ala’a Sabbagh. They had first met ten years earlier, when Sabbagh was 12 years old and sitting in the rubble of his home after the army demolished it. Now Sabbagh was the leader of the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade in Jenin, and Zacharia Zubeidi was his deputy. Zubeidi’s mother, Samira, had been killed a month before the battle began: she was sitting on her porch when an Israeli sniper, possibly mistaking her for her son Taha, shot her; Taha was killed a few hours later. The Stone Theatre, on the top floor of Samira’s home, was demolished.

By night Juliano accompanied Sabbagh and Zubeidi on patrols, ate with them and slept in their hideouts. He spent seven months with men who were on Israel’s hit list. Sabbagh was killed by a helicopter gunship in November 2002. Zubeidi, who replaced him at the head of the Al-Aqsa Brigades, soon became known in Israel as the Black Rat for his skill in dodging the army’s attempts to kill him. In spite of his easy rapport with people in the camp, Juliano remained suspect, as an Israeli citizen, even among the fighters who were his friends. ‘They trusted him and didn’t trust him,’ Or told me. ‘It was exciting for him.’

Arna’s Children was released internationally in 2004. It is a raw and upsetting film – above all, a son’s elegy for his mother. We first see Arna at a checkpoint protesting against the closure of Jenin. She expresses her anger at the occupation and her belief that music and theatre can show her students a way out of the occupation. In fact, she is raising the next intifada’s martyrs. Ashraf, Yusuf, Nidal, Ala’a and Zacharia will all become fighters; only Zacharia will survive. Their decision to fight, as shown in the film, is as inevitable as it is tragic: they are patriots defending their homes, not Islamic zealots; their cause, it suggests, is no different from Arna’s. The film is not an inspirational tale but a portrait of failure: you see the weakness of non-violent resistance in the face of a violent occupation.3

The film turned Juliano into a celebrity on the radical left. But he was having a hard time getting work on the Hebrew stage, partly because of his politics, but also because of his reputation for destructive behaviour. One night he walked off the stage of the Habima Theatre and punched a man who called him a traitor. He had never been more famous, or less employable. He needed a break. He took his four-year-old daughter to India on a motorcycle trip; Milay sat in a basket he’d made for her. Four months into the trip, Or joined them for another two months. But when they returned, Or moved back to Tel Aviv with Milay, and Juliano stayed in Haifa. Again he began to spin his wheels. Lihi Hanoch, his cousin, encouraged him to leave Israel, maybe move to New York, where he’d won the prize for best documentary at the Tribeca Film Festival. Instead, he went back to Jenin.

Arna’s Children had been a success in the Jenin camp, where people had never seen themselves on film, much less depicted as freedom fighters. Juliano showed the film in a football stadium before an audience of more than three thousand. Every time one of the shaheeds – the martyrs – appeared on screen, the audience roared, and members of the Al-Aqsa Brigades fired their guns into the air. ‘You’re shooting for nothing!’ Amira Hass, the legendary Haaretz correspondent based in Ramallah complained to Zubeidi. ‘How much does each of those bullets cost?’ The camp’s resistance to the army during the invasion had been heroic, Hass told me, ‘but at the same time, men like Zacharia were living out a fantasy of armed struggle, where the very use of explosives, whether bullets fired in the air or human bombs exploded in buses, was glorified without thought for their long-term effects.’ Arna’s Children, she worried, ‘might bolster the cult that Zubeidi and his friends were building around themselves’. But it had its practical uses. It raised morale, and enabled young fighters to win positions in the Palestinian Authority – among them Zubeidi, who would soon collect a salary from the Ministry of Prisoner Affairs. It also helped to make them stars inside the camp, Zubeidi most of all.

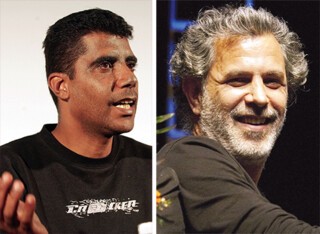

Zubeidi first came to prominence in Israel a year before the release of Arna’s Children, when he gave an interview to Haaretz. It was the beginning of a strange romance between the Israeli press and ‘Israel’s number one wanted man in the area’, alleged to be responsible for the deaths of at least six Israeli civilians. Zubeidi relished the spotlight, and made himself available to reporters. He was a loose cannon who admitted he was no good at following orders. He spoke warmly of Arafat but otherwise expressed contempt for the PA, Mahmoud Abbas in particular: ‘Abu Mazen doesn’t even control his pants,’ he said. (Still, he had no compunction about drawing a PA salary: like many of his fellow militants, he had become dependent on an organisation whose existence he saw as humiliating to national aspirations.) He was comfortable among Israelis, and said his struggle was with the occupation, not with Jews. He spoke choppy but fluent Hebrew, which he’d learned in prison. He had an easy smile, a boyish charm.

Born in 1976, Zubeidi came from a family of militants. His father had been an English teacher, but was banned from teaching because of his membership of Fatah; he worked in an iron foundry while Samira worked with Arna Mer. Zubeidi went to the children’s centres and acted in Stone Theatre productions, but school never held much interest for him. He spent his adolescence in street battles with Israeli soldiers, and in prison, where he joined Fatah. When the Oslo Agreements were signed in 1993, he joined the PA police, but quit after a year. Under the name Jul Darawashe, he made a living in Israel as a contractor. When his cover was blown and he was deported, he turned to stealing cars in Israel and selling them in Jenin, until he discovered a new talent: making explosives. (Once, a bomb blew up while he was making it, leaving his face dark and pock-marked.) Sleeping in temporary hideouts, never far from his pistol, Zubeidi was always a step ahead of the Israelis. At least 14 Palestinians were killed in Israeli operations against him. His ability to outwit his pursuers made him a local hero. By the time Juliano came to the camp to show Arna’s Children, he was the most powerful man there.

Not long after the premiere, Juliano and Zubeidi started talking about relaunching Arna’s project. It was their acquaintance Jonatan Stanczyk, the son of a Polish-Jewish father and an Israeli mother brought up in Stockholm, who drew up the plans for the Freedom Theatre. The three of them opened it in February 2006. They knew that the camp was a quixotic location; most people there had never even seen a play performed. But that made it all the more exciting. Juliano would be the artistic director, Stanczyk the operations manager, while Zubeidi would protect the theatre from anyone who threatened it. Zubeidi’s support was indispensable: Juliano and Stanczyk – both outsiders, both Jews – could never have worked in the camp without his blessing and the legitimacy he conferred. But Zubeidi was a wanted man and in no position to defend the theatre from Israel’s threats: that was Juliano’s job. He disarmed soldiers by addressing them in Hebrew; some recognised him from the movies.

Stanczyk, who had made £50,000 playing the Stockholm real-estate market, supplied the start-up capital; the rest came from screenings of Arna’s Children. Most of the original employees were volunteers; Stanczyk refused a salary. Juliano and his partners rented a building, and put up photographs of Che, Darwish, the novelist Ghassan Kanafani and Arna Mer in her keffiyeh. For the first few months, they slept on mattresses in the same room; Juliano hardly left the camp.

Juliano was startled by the changes in the camp since his mother’s day. The physical damage had been repaired, but most children showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder. Thanks to Israel’s closures, Jenin was more isolated than ever; thanks to the rise in Islamic piety, it was more internally repressive. The inhabitants now suffered from two occupations: Israel’s, and what Juliano called a ‘cultural-religious occupation’ imposed from within. Juliano wanted to fight both of them. But in order to fight the second, he needed to win people’s trust. And the camp was inevitably suspicious of outsiders, especially those who made an issue of their good intentions. It was also swarming with informers. Even Zubeidi’s sponsorship could turn out to be a mixed blessing: it marked the theatre as a Fatah project at a moment of intensifying Fatah-Hamas rivalry.

Juliano worked hard to woo the camp, and to remain somehow above the fray. Using his privileges as an Israeli citizen, he turned himself into a one-man relief organisation. He brought food and medicine to people’s homes. He drove pregnant women through checkpoints to hospitals in Israel, and children who had never seen the sea to the beaches of Haifa. If someone tried to shake him down for cash, he would give them a small job. In deference to the camp’s ways, he never drank outside his house, and threw away his empty whisky bottles in Haifa. When women from outside the camp came to work in the theatre, he insisted they wear long sleeves. He lived very simply, and refused to install an air conditioner in his house. He went to great lengths to prove that he was not beholden to Fatah, in spite of his alliance with Zubeidi.

The idea that, even under occupation, Palestinians could improve their situation, was central to Juliano’s pitch. ‘Israel is destroying the neurological system of the society,’ he said, ‘which is culture, identity, communication,’ but ‘if you’re going to keep blaming the occupation for all the problems of the Palestinians, you’re going to end up in the same situation we’re in today.’ He was careful not to denounce the armed resistance; that would have been heresy in the camp. But the next intifada, he declared, ‘will be cultural’. Perhaps art could succeed where violence had failed. ‘We have to stand up again on our feet,’ he said. ‘We are now living on our knees.’

The ‘we’ was new. More and more Juliano spoke of himself as a Palestinian. The story of how he came to Palestine became an inspiring conversion narrative. ‘He never hid his history, the things that might make people uncomfortable,’ Khulood Badawi, a friend in Haifa, told me: he spoke of being ‘a killer’ in the paratroopers, of his mother’s work at the Stone Theatre, of the political awakening that led him back to Jenin. ‘When I left Haifa,’ he said, ‘I left Israel. I left my work, I left my society, I left my friends. I live here.’ But Juliano never really left Israel, or his friends there: at the weekend, he was often in Haifa or in Tel Aviv. The story he told about his break with Israel was ‘mainly an instrumental declaration’, Ruchama Marton, the founder of Physicians for Human Rights, told me. ‘He had to say this to work in Jenin. In the same week I would see Juliano one day in Tel Aviv and another in Jenin. Was he a different person? Sure, he spoke Arabic there and Hebrew here. It’s not that he was lying. It was true and not true at the same time.’ The performance went over well enough. Juliano was the son of a local saint, and he pledged to continue her work, but he had larger ambitions than his mother: he wanted to transform the camp, not just to serve it. His ultimate aim was to train a group of professional actors, to stage productions that would be both artistically serious and politically provocative, and to create an independent media centre for Palestinians in the West Bank and in Israel. Jenin was a base of operations, not a final destination.

He found his students by wandering through the camp, introducing himself to people and describing his vision. Some of the actors he attracted had been fighters, others were thieves: hard cases, just as he had been. Of his first six students, five were from Jenin, two were girls, and all faced ferocious opposition from people in their communities, for some of whom the theatre might as well have been a brothel. It was a shameful place where boys and girls mixed; a place, as one visitor remarked to me, that ‘smelled of sex’. Outsiders called the student actresses whores. One father threatened to disown his daughter. For the boys it wasn’t much easier. Juliano was a tough teacher, but he was also careful to build up his students’ confidence. He told them they would be stars. And he paid them the ultimate compliment in Jenin: ‘You’re not actors,’ he said, ‘you are freedom fighters.’

But these ‘freedom fighters’ couldn’t perform without the cover of Zubeidi and his friends in the Al-Aqsa Brigades. Juliano was proud of his closeness to Zubeidi and the resistance; he could hardly object if its lustre rubbed off on the theatre. It was a major attraction for volunteers from Europe and America, who descended on the theatre as if it were a revolutionary base. But Juliano was trading on his relationship to the resistance while promoting a non-violent alternative. ‘Juliano understood that the methods of the Second Intifada had been a complete failure for the Palestinian cause,’ Jenny Nyman, the Finnish woman he married in 2007, says. ‘Even though he never spoke against the armed struggle, at the same time he said: “Look what’s happened to you. Isn’t it time to take a break and build up the society again?” He wanted Zacharia to be a part of this. Zacharia was a big reason Juliano went back to Jenin, and he saw the theatre as a way of saving him.’

The young people who came to study in the theatre were looking for a form of resistance that would allow them to live, rather than die as martyrs. This went against the grain in Jenin. ‘To be wanted by the army, to be a hero, was everyone’s dream,’ a student called Faisal Abu Alheja told me. ‘But when I went to the theatre, I said, this is a dangerous idea: it means we want to die. How can we have freedom if we die?’ In the theatre, he could ‘think without Fatah, without Hamas, without Islamic Jihad’. Juliano forged strong relationships with young men whose fathers had been killed or spent long periods in prison. Mustapha Staiti, the son of Nawal Staiti, who worked with Arna Mer, was one of them. His father, Mohamad, a Fatah activist, had been in prison for much of his son’s childhood. Under torture and other forms of physical duress, he’d lost much of his sight. He found god, and defected from Fatah to Hamas. After his release in 1995, he beat his children, and tried to get his daughters to cover themselves. Mustapha drifted away from his family and dabbled in radical Islam. He thought of becoming a fighter like his father, he told me; he was looking for ‘a way to get killed and just finish the story’. It was then that Juliano re-entered his life, and promised his mother that he would look after her son. He took Mustapha to the theatre, gave him a video camera, and introduced him to film-making. ‘Juliano took me under his wing, and I put down everything. My life became Juliano. He knew how we felt, he knew how to communicate with us, and he found an energy in the camp that he didn’t find elsewhere.’

It was at night, he said, drinking whisky with Juliano, that he learned the most. Juliano and Zubeidi shared a house, first in the camp, later in the city, where a number of staff members also rented rooms. There members of the acting troupe and other friends of the theatre were introduced to the pleasures of alcohol and hash, and met radical Israelis and foreigners. They were getting their first glimpse of a world beyond Jenin. It was a world Israel prevented them from entering, and the local enforcers of the cultural occupation didn’t want them to see it either. Though the parties took place behind closed doors, rumours began to ripple through the camp. Girls and boys dancing on stage, fighters putting down their weapons to become actors, and now parties with drugs and sex: to some, it looked as though Juliano had come to foment a youth revolt. It was all part of an Israeli plan to weaken the resistance. One former Fatah activist told me he first understood this when he heard that children at the theatre were being taught about the Holocaust: ‘First the Israelis destroyed the camp, then they gave us the theatre.’

The charge that the theatre was a foreign project was hard to rebut. Although the administrative staff was largely from Jenin, most of the people running it were foreigners, and both Juliano and Stanczyk were Israeli citizens. The theatre’s stance was unusually radical for an NGO in Palestine. It refused to criticise the armed struggle, or to parrot the PA’s rhetoric about the peace process, positions that lost it some potential funding. It attacked the PA’s collaboration with Israel, and described itself as part of a struggle against occupation rather than another ‘capacity-building’ organisation. Yet the Freedom Theatre depended as much as other NGOs on foreign money, and on the goodwill of its many guests from abroad. It had radical cachet because it was located in the camp, but its real roots lay elsewhere. Juliano conceived of the theatre as a kind of revolutionary training base for soldiers in the ‘cultural intifada’, but it looked more like a bohemian oasis in the midst of the camp’s miseries.

Juliano was convinced that once people saw the results of his work, they would embrace it. His charisma worked wonders when he went abroad to raise money. His most ardent supporters were a group of ageing New York radicals led by Constancia Romilly, the daughter of Jessica Mitford and the ex-wife of the civil rights leader James Forman, and Dorothy Zellner, a veteran of the Student Non-violent Co-ordinating Committee. Friends from the civil rights era, and both red-diaper babies, Romilly and Zellner met Juliano in 2006 at a screening of Arna’s Children at NYU. The two women set up the Friends of the Freedom Theatre, modelled on the support groups for SNCC. They held a fundraiser at the West Village flat of Romilly’s friend Kathleen Chalfant, a well-known New York actress. Juliano talked about his mother’s theatre, and about his own efforts to rebuild a shattered community through art. His ‘most effective fundraising tool’, Chalfant said, was to offer a non-violent way of opposing the occupation. James Nicola and Linda Chapman, the heads of the New York Theatre Workshop, were excited by Juliano, and became sponsors of the Freedom Theatre. Nicola was impressed that ‘Juliano’s definition of freedom was much bigger than freedom from occupation’, embracing women’s liberation, freedom from religious oppression, personal and sexual freedom. Everyone who met Juliano in New York was beguiled: Danny Glover, Tony Kushner, the philanthropist and writer Jean Stein. Julian Schnabel cast him as a sheikh in Miral, Juliano’s last performance on film. Eve Ensler invited him to stage The Vagina Monologues in Jenin. In a city of hyphenated identities his mixed identity made him all the more attractive, and more trustworthy. The theatre became a popular cause for celebrities on the left: Vanessa Redgrave, Maya Angelou, the film producer James Schamus, Judith Butler, Slavoj Žižek, Noam Chomsky and Elias Khoury.

Juliano urged supporters from the West to come to Jenin. Romilly often stayed with him in his home in the camp. One night Israeli tanks rolled up at three in the morning, and ordered everyone out of their houses. ‘Juliano came downstairs in his boxer shorts, and said: “We’re not going out. They know that I’m here, and they know that I have foreign visitors.” He was very reassuring. We always felt safe.’ Juliano introduced her to Zubeidi. At the time, he was a wanted man, and still lived underground. In the early days of the theatre, he kept a low profile: the presence of a ‘terrorist’ might discourage potential donors, Nyman told me. But he provided evidence of the theatre’s connection to the resistance, and some guests became enamoured of him. The LA philanthropist Charles Annenberg, charmed by Zubeidi, wrote the Freedom Theatre a $200,000 cheque, and made a rapturous documentary about his new friend, Nobody Is Born a Terrorist. ‘It was an absolutely terrible film,’ Nyman says, ‘but he gave us money and became a friend.’ (He was one of several wealthy American Jews supporting the theatre; for Arabs, Nyman says, Juliano was ‘too Jewish’.)

In July 2007, Zubeidi came out of the shadows: as part of an agreement between the PA and Israel he promised not to engage in armed resistance in return for having his name removed from Israel’s wanted list. Juliano saluted his decision. Zubeidi, he said, ‘left the armed resistance after being inspired by the theatre, deciding that the only way forward was to join the cultural struggle against the Israeli occupation’. In fact Zubeidi had little choice. He was one of 178 Fatah militiamen who accepted the amnesty; he could hardly defy the Fatah leadership. It was part of a series of political developments that transformed Jenin’s political landscape. The PA, which had lost control of Jenin after the 2002 invasion, stepped up its efforts to impose itself on the camp – and to take over ‘security’ responsibilities from Israel. In 2008, hundreds of PA security officers, funded by the US and trained in Jordan, entered Jenin, rounding up militants. The Jenin Development Plan was sweetened with economic and agrarian assistance and eased security restrictions for local merchants. Before long, the ‘reformed’ security services in Jenin were fighting each other over territory and patronage.

Zubeidi was now free to sleep at home for the first time in five years, though he wasn’t allowed to leave Jenin. But signing the amnesty did little to enhance his reputation inside the camp. Now that the Israelis were no longer giving him chase, his talent for survival counted against him. (‘In Jenin you’re not innocent until you’re dead,’ one man told me.) Perhaps, some whispered, Zubeidi had survived because the Israelis wanted him alive; perhaps he’d been an informer all along. There had always been questions about his courage during the Battle of Jenin. Some of his critics cited a scene in Arna’s Children as evidence: his predecessor as leader of the Al-Aqsa Brigades, Ala’a Sabbagh, who surrendered a week into the 2002 invasion, accuses Zubeidi of hiding with his group rather than continuing the fight. ‘At least I didn’t surrender,’ Zubeidi replies, declaring that he would rather die than surrender. ‘If you wanted to die, why didn’t you shoot the soldiers?’ Sabbagh fires back. ‘You pretended to be dead.’ Ferocious recriminations about his acceptance of the amnesty came from Tali Fahima, an Israeli radical who had converted to Islam and spent nearly three years in prison for visiting Zubeidi in Jenin, and the attacks from Hamas, which had not ended its armed resistance and saw the amnesty as a betrayal, were more damaging still.

Even Gamal Abdel Nasser, Zubeidi said, ‘admitted his defeat, so why not me?’ And he continued to attack the PA: ‘They are whores. Our leadership is garbage.’ But there was no denying that the amnesty had damaged his heroic image. His biggest defender was Juliano, and he drew closer to him, even as his friends in the Al-Aqsa Brigades warned him not to be ‘Juliano’s man’. (‘Don’t ask me to hold a guitar against an M16,’ a former Fatah activist in Jenin told me when I asked him what he thought of the theatre.) The theatre was connected to influential people far outside Jenin, and Zubeidi had always fancied being on a wider stage. ‘Zacharia is like Juliano,’ Abed Qusini, a journalist in Nablus, told me. ‘He used Juliano as much as Juliano used him. Juliano gave him a big name, and he wanted to be a leader in front of the world.’ Not that he had much to do with the theatre’s programming. ‘Let’s face it,’ Nyman said, ‘he’s not a culture person.’

Not long after he was amnestied, Zubeidi built a stone and marble mansion in Jenin City with a view of the camp. It was in a neighbourhood called the Mountain of Thieves; many of the residents are PA officials. No one could explain how Zubeidi was able to build his mansion on his wages from the Ministry of Prisoner Affairs. The PA suspected that, like many former militants, Zubeidi was selling guns. During the Second Intifada, Jenin had become an arms warehouse, and no one had better access to it than Zubeidi. He is believed to have invested his profits in real estate in Jenin and Nablus. He divided his house into flats, and became a landlord for a number of employees of the theatre, including Juliano and al-Raee. It was safer for them in the hills.

In the spring of 2009, the theatre staged Animal Farm, and Juliano realised he had enemies, not just critics, in the camp. The production was designed to shock. Actors appeared on stage dressed as pigs, violating Islamic taboo. In the last scene, army officers speaking Hebrew came to trade with the pigs: a dagger aimed at the Palestinian Authority. One night, someone tried to set the theatre on fire; later the same evening, another Western-supported cultural organisation in the camp, the Al-Kamandjâti Music Centre, was burned to the ground. Soon there were anonymous leaflets denouncing the theatre as a plot by Jews and foreigners to ‘denigrate the memory of our martyrs’. Juliano responded by taking his case to the community. He organised public meetings; he spoke to the local imams. ‘We faced our critics,’ al-Raee said. ‘We invited them to the theatre and explained what we were doing.’

The attention the theatre was generating abroad made its work that much more difficult. The PA felt snubbed when in 2009 David Miliband came to the theatre without consulting them. A perception arose that the theatre was rich, though its operating annual budget never exceeded $450,000 dollars, modest for an organisation of its size. Juliano had never handed out money, but he had gone out of his way to help people in the camp. According to Jamal Zubeidi, Zacharia’s uncle, Juliano’s reputation as a rainmaker created problems when he turned down people’s requests: ‘So long as people thought he was supporting them, they saw him as a Palestinian. If they stopped thinking it, he became a Jew.’ The problem wasn’t corruption, Nyman says, but its absence: ‘After Oslo, the whole NGO business became extremely corrupt, and basically meant lining your pockets and lining the pockets of your friends. The Freedom Theatre wasn’t like that. We were approached directly by Fatah officials who wanted a slice of the cake, but Juliano refused bribes.’ The theatre’s staff believed the arson attempt was carried out by a disgruntled Fatah member, not an Islamist.

Juliano’s friends in Jenin told him the theatre would be safer if he moved it from the camp to the city. The German-sponsored Cinema Jenin was there, and though it had had its problems, they hardly compared with the theatre’s. With Zubeidi acting as his front man – as an Israeli, Juliano couldn’t purchase land – Juliano bought an empty lot in the city and began to build what he hoped would be a national theatre, one as innovative and influential as the Habima Theatre in Tel Aviv. He talked about his plans as if they were a fait accompli, though he had yet to secure a permit from the city. The theatre in the camp, Juliano wrote in a letter to a group of supporters in July 2010, would be transformed into ‘an interactive TV studio which will serve all Palestinian artists, from Gaza, the West Bank, East Jerusalem, Israel and the Palestinian diaspora, without the supervision of political parties, and certainly not of Israel’.

The theatre’s work with children – the sort of unglamorous work that had won Arna so much love – began to suffer. Juliano complained that he was tired of ‘social work’: he wanted to create real art, not plays for children. His behaviour set off ‘a huge upheaval in the theatre’, Romilly told me. Stanczyk quit and returned to Stockholm. The friends of the theatre in France withdrew their support, and the board in Jenin resigned. Frustrated by the resistance to his plans, Juliano spent more time in Haifa, where he directed a production of Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden. He took his friends in the cast to see the theatre in Jenin; he spoke of setting up a Freedom Theatre branch in Haifa and leaving the theatre in Jenin in the hands of local Palestinians. In Haifa he could escape from the scrutiny of the camp. For now, though, he told Amer Hlehel, one of the actors in Death and the Maiden, he had to go back to Jenin. ‘All my projects would be a lie’ otherwise.

His next production with the Freedom Theatre premiered in February 2011. It was an adaptation of Alice in Wonderland, and told the story of a girl who refuses to marry the man her family has chosen for her. Juliano advertised the show by putting the actress Maryam Abu Khaled, dressed as the Red Queen, on the roof of his car with a megaphone and driving her around the camp. Some men told her never to show her face in their neighbourhood again; she was afraid she might be stoned. But more than ten thousand people came to see the play, many of them from the camp. ‘There were kids in the camp who’d already seen the play who were staging demonstrations to see it again – Jenin-style demonstrations,’ Nyman told me. ‘It looked like we were becoming a big force in the community.’

Not everyone in the camp was pleased by Juliano’s success, and a stark reminder of his outsider status came when Jenin City refused to give him a permit to build the new theatre. But Juliano didn’t relent. In early March 2011, a German acting teacher at the theatre, Stephan Wolf-Schönburg, proposed a production of Frank Wedekind’s Spring Awakening, and Juliano agreed. The 1906 play, a celebration of youthful sexual revolt, has been banned time and again for its treatment of homosexuality, incest, child abuse and suicide in fin-de-siècle Germany. Nyman thought the idea was ‘just crazy’, but Juliano reminded her that Wolf-Schönburg had connections to the Goethe Institute and other potential sources of funding. He didn’t want to discourage him.

Wolf-Schönburg, who is gay, told me he expected the actors at the theatre to be ‘as interested as we were when we were young. Puberty, growing up, being in opposition towards parents and society.’ But it turned out to be harder than he’d thought when rehearsals began on 14 March. Some actors pulled out, and talked about the play in the camp; there was also opposition from members of the local board. Hlehel warned Juliano that he would be ‘committing suicide’ if he went ahead with it, but Juliano replied that ‘putting on this play in Jenin would be a revolution.’ He had second thoughts, however, when an anonymous leaflet appeared denouncing him as a ‘Communist, an atheist and a Jew’. If the theatre didn’t stop the production, it said, ‘we will be forced to speak in bullets.’ On 28 March, Juliano, who was in Ramallah directing a production of Ionesco’s The Chairs, cancelled Spring Awakening. A week later, he returned to Jenin, where his killer was waiting for him.

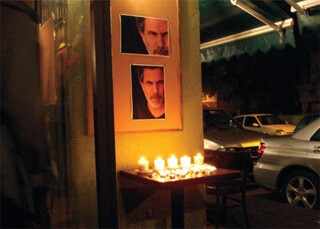

Inside the theatre, Juliano was mourned by his colleagues and students, but in the camp people were silent. The streets weren’t flooded with people holding up his picture or waving Palestinian flags, as they usually are when a martyr dies. When a group from the theatre went to the city to light candles in his memory, people asked why they were crying for a Jew. The camp seemed to be in a hurry to forget him. In Haifa, he was given a martyr’s funeral. The service was mostly in Arabic, the only flags on display were Palestinian, and speaker after speaker – including Zubeidi, who addressed the crowd via mobile phone – praised him as a Palestinian hero.

The investigation of Juliano’s murder has been fruitless. It wasn’t clear who was responsible for investigating the murder of an Israeli citizen from a mixed Arab-Jewish background, living as a Palestinian in Jenin. Although they had collected all the evidence at the crime scene, the Israelis told Abeer Baker, Nyman’s lawyer, that pursuing the case would be difficult because the murder took place under Palestinian sovereignty: Jenin is in Area A, formally under the jurisdiction of the PA. (‘Suddenly the Palestinians have a state!’ she said.) In May 2013 she received a letter from the authorities: ‘Unfortunately there is no development in this case that can help us bring people to justice.’

The lack of progress has raised suspicions of a cover-up by Israel, but Baker is sceptical. The problem, she said, is indifference: ‘Juliano isn’t a settler with political power. Deep inside they don’t think he was killed because he was a Jew.’ The PA has been no more eager to find the killer. Shortly after the murder, it arrested a man with ties to Hamas, but he was soon released. Palestinian security conducted a preliminary investigation, and apparently concluded that the murder involved issues of money and power in the theatre, but it made no further arrests. Baker speculated that the PA has shied away from the case because of ‘Fatah issues, or problems in Jenin over weapons’. The PA’s impotence has left Baker, a Palestinian citizen of Israel and a human rights lawyer, in the awkward position of ‘begging the Israelis to indict a Palestinian’. ‘We don’t care if the suspect is tried in Israel or the Occupied Territories,’ she said. ‘He’s a murderer, and who said trials are any fairer under the Palestinian Authority? But we do want the suspect to be interrogated fairly, not placed in a Shabak cell and tortured. It’s what Juliano would want. What am I supposed to do? Ask the Israelis to invade Jenin?’

The Israelis have been much more active in Jenin since the murder. The Freedom Theatre has been a frequent target of military raids in the past two years. Most of the Palestinian members of the theatre staff, and many of the actors, have been taken in for questioning, some for a few hours, others for weeks. Rami Hwayel, a shy young actor, was arrested at a checkpoint outside Ramallah; he spent 31 days in prison. In June 2012, al-Raee was woken up at 3.30 a.m. by Israeli soldiers at the house he shared with Zubeidi and taken to a nearby detention centre. He was interrogated for 48 hours, tied to a chair, and spent forty days in prison. His interrogators accused him of plotting Juliano’s murder with Zubeidi. When he emerged from prison, people in Jenin were friendlier; the ordeal had gained al-Raee, who grew up in a camp outside Hebron and was always viewed with suspicion in Jenin, a bit of street credibility.

Zubeidi was never taken in for questioning by the Shabak. It was a strange omission. Zubeidi was Juliano’s guardian angel, and no one had grieved his death more openly. A year after the murder, at the tenth anniversary of the invasion of the Jenin camp, he tried to put up a poster of Juliano beside the posters of the fighters who died fighting the Israeli army; when other former fighters took down the poster, he flew into a rage. Today, some people think this was a carefully staged performance. Everyone said that Zubeidi was the eyes and ears of the camp, so Juliano’s friends expected him to live up to his promise and find the killer. But he very soon lost interest in the case, or so it seemed; when asked about it, he said it was in the hands of the authorities. In Ramallah, ex-comrades of Zubeidi told Tali Fahima that he was behind the murder. Juliano, they claimed, had discovered that Zubeidi had been diverting money for the theatre in the city to his own real estate investments. The Shabak wasn’t lifting a finger because Zubeidi had always been a useful source of information about the camp. Many of Juliano’s friends in Israel, both Jews and Arabs, have come to believe that Zubeidi knows more than he’s letting on. Some, Or included, believe he conspired in his best friend’s assassination. (She also claims Juliano was carrying a suitcase filled with cash that he’d taken out of his safe in Haifa two weeks earlier, but no suitcase has been discovered.) Others suggest that the killing may have been a message to Zubeidi that he ‘no longer controlled the camp’, which would explain why he expressed such guilt after the murder. But Zubeidi has kept his silence, and discouraged others from probing. When he heard that Or was making inquiries about him in Ramallah, he warned her not to speak about him behind his back.

Zubeidi has spent most of the past year as a prisoner of the Palestinian Authority. His troubles began on 28 December 2011, when Israel revoked his pardon for unstated reasons and the PA recommended that he turn himself in in order to avoid arrest, or worse. He declined the advice, but in May 2012, when Qaddura Musa, the Jenin district governor, died of a heart attack after gunmen opened fire on his home, the PA put him in jail. One of the guns allegedly used in the raid was found in Zubeidi’s home, though he maintains his innocence. He went on a hunger strike, supported by a petition drafted by the theatre and its friends in the West. He was released in October 2012 and early this year returned to PA custody, saying he would otherwise risk assassination by Israel. Few I spoke to in Palestine took this claim seriously. ‘If Israel truly wanted him, it would have no difficulty reaching him where he is,’ I was told. He’s in a facility outside Ramallah, too comfortable to be called a prison, with access to email, Facebook and his mobile phone. He receives visitors, and is in regular contact with his colleagues at the theatre. No one there believes that Zubeidi could have been involved in Juliano’s murder. Under PA custody, with his amnesty revoked, he is still an asset to them.

When I spoke to him by phone, he claimed the Shabak had hired a local hit man to kill Juliano because of the growing success of ‘cultural resistance’. It’s a view you often hear inside the theatre, but almost never outside it, certainly not in the camp. The rumour in the camp is that Zubeidi supports the theatre because it has supported him with a salary and other unnamed ‘benefits’. When I mentioned this to him, he said I must have been talking to people in the PA. (I hadn’t.) He praised Juliano for giving ‘an image of the Palestinian fighter as a human being, not a terrorist’, and said: ‘The seeds that Juliano planted here are growing.’

The theatre is indeed flourishing. ‘The miracle of the Freedom Theatre is that it continues to exist,’ Kathleen Chalfant told me. But one could also argue that the theatre has benefited from Juliano’s absence. Under Juliano it was wild, volatile and inspired; it has become calm, measured and diligent under Stanczyk, who returned from Stockholm the day after Juliano was killed, and resumed his role as general manager. The theatre has raised its international profile, sending productions on tour in Europe and the US; it has also expanded its activities throughout the West Bank. Although Israel has continued to harass it, the anonymous threats have subsided, a modus vivendi has been established with the camp, and an eerie sort of normality has set in. For Juliano’s old students, this shift in direction feels like a betrayal of their hero. One day a group of them were grumbling about the theatre in the courtyard. It was less provocative, less radical, less ambitious, they said. There were hardly any girls on stage. But the theatre couldn’t be blamed if parents had taken their daughters out after Juliano was killed. And under Stanczyk’s leadership, the entire enterprise has acquired something Juliano lacked, something he fought against all his life: a sense of limits. Most of the photographs of Juliano in the theatre’s offices have now been taken down. But Nabil al-Raee told me he can’t go to work without thinking of him. The theatre remains ‘a haunted place’, his wife said. Some of Juliano’s friends in Haifa haven’t visited the theatre since the murder; they don’t feel welcome in the camp. Until the killer is found, Mishmish Or said, the theatre will be ‘nothing but a crime scene’. Jenny Nyman used to feel this way too. She was angry at the theatre for continuing its work in a ‘tamer way’. ‘Jul liked to say it’s better to die on your feet than live on your knees. I thought the theatre was just going down on its knees, like it’s OK to shoot me if you think I say the wrong thing.’ But a few months ago, she went back to the theatre. What struck her most was how quiet it seemed without Juliano.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.